Jeff Gundy, Fulbright Scholar

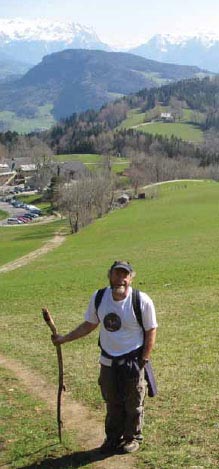

Jeff Gundy, Ph.D., professor of English, spent the spring 2008 semester on sabbatical, lecturing at the University of Salzburg in Salzburg, Austria, after being awarded a Fulbright Scholar grant. He is one of 800 U.S. faculty and professionals to travel abroad through the Fulbright U.S. Scholar Program. Gundy taught three courses in the American Studies department and did some writing and traveling.

Where do I start, describing four months in Salzburg? I worked quite hard, some of

the time, teaching literature and American Studies courses at the University of Salzburg.

But I was freed of most of my usual university responsibilities, and we had only a

one-bedroom apartment to care for— no yard, no garden, no driveway to shovel, no plumbing

to repair and no cars to keep running. Much of the time, we felt blissfully free to

wander downtown, take in a concert, go for a walk through the meadows below the nearby

mountain or plan an excursion to one of the dozens of places we'd been told we just

had to see.

Where do I start, describing four months in Salzburg? I worked quite hard, some of

the time, teaching literature and American Studies courses at the University of Salzburg.

But I was freed of most of my usual university responsibilities, and we had only a

one-bedroom apartment to care for— no yard, no garden, no driveway to shovel, no plumbing

to repair and no cars to keep running. Much of the time, we felt blissfully free to

wander downtown, take in a concert, go for a walk through the meadows below the nearby

mountain or plan an excursion to one of the dozens of places we'd been told we just

had to see.

My wife, Marlyce, wangled a leave from her job to come along, and she did most of our travel planning. On breaks and long weekends (my classes were all on Tuesdays and Thursdays), we often took off via train or bus. We walked the streets of famous cities all over central Europe: Vienna, Florence, Venice, Prague, Krakow, Budapest. We saw less famous but fascinating cities, villages, lakes, as well, and too many mountains, rivers, castles and picturesque houses to number.

Much of our time, though, was spent in Salzburg, one of Europe's most scenic and culturally rich, mid-sized cities. We learned quickly that Gemütlichkeit—hard to translate, but perhaps a combination of "comfort" and "living well"—is the key to life in Austria. It involves taking time for conversation with one's neighbors, extended meals at the plentiful local restaurants and tree-shaded cafes, coffee and sumptuous pastries at the famous coffeehouses downtown. Austrians take pride in blending Germanic efficiency with Mediterranean ability to savor the moment.

Americans know Salzburg as the Sound of Music city, but locals regard movie locations like the Mirabell Gardens, the Leopoldskron Palace and the Nonntal nunnery as part of the city's long heritage, not just scenery for a Hollywood movie. The Festung, the massive fortress that looms on a steep hill in the center of the city, is an enduring reminder of the powerful archbishops who for generations were both the religious and political rulers of the region.

The city is still quite Catholic—the many cathedrals are filled for masses, as well as busy with tourists—and in close touch with its remarkable history. But old and new blend in the everyday lives of Austrians. They use the efficient bus and train networks or ride bicycles on the network of paths that runs throughout the city, and we did the same.

My work at the university was both familiar and sometimes surprising. In my literature courses, I found students eager to encounter American poets and novelists (Allen Ginsberg's Howl was a class favorite in my poetry seminar, and so was African-American poet Lucille Clifton). They quickly found connections between our texts and their own experiences. When my small Midwestern Writing class read part of Sinclair Lewis' Main Street, the animated discussion of smalltown life in Austria and America went on long after class was supposed to be over.

More than half of my large North American Civilization class had visited the U.S., and they were closely following the Democratic primary battles. Most were troubled by recent American foreign policy, but enthused about American movies and popular culture. Often they knew little of American history beyond the sense that slavery and the treatment of Native Americans were very bad things, but most were eager to learn, especially from a "real" American like me who was not always quick to defend every aspect of American life.

Students at the university appreciate the low tuition—less than 400 euros per semester (roughly $600)—and the generally high quality of instruction. They complain, though, about the difficulty of scheduling classes and getting advice on their programs of study. I often thought of the extensive Bluffton system of academic, social and religious support for students as I tried to counsel perplexed young people about their courses of study.

We returned from Salzburg with a lifetime of memories. Biking along the Salzach River with the mountains on all sides; walking the streets of Franz Kafka's Prague (where we slept within a block of his old school); waking in Venice to watch two men lounging and talking in their doorways, just across a little canal from our room; crossing the Chain Bridge across the Danube on foot from Pest to Buda and back again; wandering through the vast, lush gardens of the

Schönbrunn Palace in Vienna one day and the equally vast ruins of the Auschwitz/Birkenau death camp two days later . . . there is no way to express quickly or simply what such experience means. Getting to know students, colleagues and others in Salzburg was equally important to us. I wish I had space to say more about the wonderful couple, Willi and Dietlinde, who were our landlords, neighbors and selfappointed guides to Austrian life.

We learned a good deal, in Salzburg and elsewhere, about how a civilized society might function. After all the disruptions and horrors of the 20th century, Austria and its neighbors seem to have found ways of providing meaningful work and a livable social structure for great numbers of their people. Especially in the former Soviet satellites, this process is far from complete, but people everywhere we went seemed optimistic and energized by their local prospects—even as they worried about larger, global issues of militarism and climate change.

I am extremely grateful to Bluffton for the sabbatical release and for years of experience that made my application possible, and to the Austrian-American Fulbright Commission for providing excellent financial and intangible support during our time in Austria.