Left: Mary Cassatt, Woman in Black at the Opera, 1877-78

center: Renoir, La Loge, 1874

Renoir's painting depicts the usual situation: at an opera or concert in France, the woman sat in the front of the balcony or box while the man sat behind her. This was so she could be seen. And here the woman's date/husband actively looks. In Mary Cassatt's version, femininity is associated with looking, with an active alert gaze. (Note that across the balcony the male is looking at her.) As Nochlin says, "She holds the opera glasses, those prototypical instruments of masculine specular power, firmly to her eyes, and her tense silhouette suggests the concentrated energy of her assertive visual thrust into space" (Nochlin 194). She holds the fan in her other hand, the object that women were supposed to wield--not opera glasses.

About a decade ago, when Faith Ringgold was about 61, she imagined herself as a young desirable woman, a model for the artist Matisse.

Ringgold, Matisse's Model, French Connection, Part 1: #5, 1991

An African American woman, she says she learned to see herself as desirable. She says: "I love playing the beautiful woman, knowing that I am steeped in painting history. . . . I ask the question. Why am I here posing like this, and what would HE think if I took out my glasses and started to read a first edition of Tolstoy's War and Peace or Richard Wright's Black Boy" (Cameron 135). Her self-definition includes both beauty and intelligence.3Frances Benjamin Johnson, in 1896 explored gender definitions in her photographic self portrait. Posed as a male, with mannish cap, cigarette and tankard, she crosses her legs in an unfeminine manner. Victorian women did not smoke, drink, or heaven forbid, show their petticoats. And Romaine Brooks, a Lesbian artist, presents herself as a dapper young gentlemen. Gay artists, similarly, have challenged gender definitions.

Center: Frances Benjamin Johnson, Self Portrait, 1896

right: Romaine Brooks, Self Portrait, 1923

Some artists critique the hallowed definitions. Two world wars and the war in Vietnam have put in perspective one definition of masculinity, too often associated with power and violence.

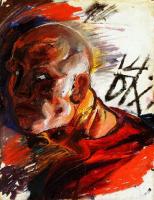

Otto Dix, Selbstbildnis als Soldat (Self-Portrait as a Soldier), 1914, ink and watercolour on paper

These soldiers look like identical automatons. Marcel Gromaire, La guerre (War), 1925 and C. R. W. Nevinson, Returning to the Trenches, 1914-15. And soldiers in gas masks look even more dehumanized. Otto Dix, Assault under Gas, 1924

Robert Arneson, Joint, 1984

Just as masculinity has often been identified with power, so too has femininity been associated with beauty. Here Audrey Flack takes on one of the most powerful icons in the second half of the twentieth century, Marilyn Monroe.

Audrey Flack, Marilyn (Vanitas), 1977-78

The painting is subtitled "Vanitas," and the painting is filled with symbols reminding us of transience and mortality--the hour glass, the watch, the full-blown rose, ripe fruits, candles burning down. If a woman defines herself in terms of external appearance, she's in for trouble--say at about 40 (50 if she's lucky).Artists take on religion too, especially when they see it as perpetuating gender oppression. Yolanda M. Lopez, a Mexican-American artist, rebels, by imagining herself as the Virgin of Guadalupe--a kind of revolutionary goddess in tennis shoes. Instead of woman as Eve, as temptress, as prostitute, she replaces patriarchal religion with a contemporary woman clutching a snake, a symbol of pagan powers. The two other panels of this triptych depict her mother and grandmother.

Yolanda M. Lopez, Portrait of the Artist as the Virgin of Guadalupe, 1978