|

For the most part thus far I have been using examples from the 15th through the 17th centuries. You may have noticed that one gender definition has been strikingly absent from my discussion: males and females as fathers and mothers. Although there was some emphasis put on the mother's role by the mid-16th century, generally the reason was to emphasize the woman's fertility, that is, her ability to provide heirs for her husband's family. |

Agnolo Bronzino, Portrait of Eleanora di Toledo, 1560These early portraits of mother and their children rarely depict a nurturing or loving relationship. |

|

|

There are even fewer portraits depicting fathers with their offspring, although Ghirlandaio did paint this absolutely wonderful portrait of a grandfather and his grandson in the 15th century. Ghirlandaio, An Old Man and His Grandson, c. 1490 |

Sometimes artists painted their own families in group portraits. |

Rubens, Rubens, His Wife Helena Fourment and their son Peter Paul, c. 1639

Anthony Van Dyck, Family Portrait, c.1620-21

|

|

|

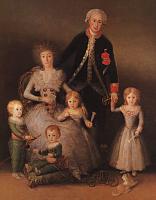

Some changes in the depictions of men and women did occur with the Enlightenment emphasis on the family. Goya's Family of the Duke and Duchess of Osuna, 1787-88, is a fairly typical family portrait of this period. (See also Kauffmann's Earl of Derby and Lady Hamilton with Son.) |

|

|

Left: Goya, Family of the Duke and Duchess of Osuna, 1787-88

center: Kauffmann's Earl of Derby and Lady Hamilton with Son, 18th century |

In Goya's painting, the father as head of the family stands, and both parents touch their children. Although they are all well-dressed, the emphasis is on the family dynamic, not a fashionable setting. Gender roles are already being reinforced: the young girls wear dresses like their mother's, complete with the fans they will learn to gracefully hold. The boys play with their toys, one of whom (far left) rides "the baton of command belonging to his father, a lieutenant-general of the Royal Armies and colonel in the Regiment of the Royal Guards" (Ribeiro 162), a reminder of the roles men are called on to perform. 1 |

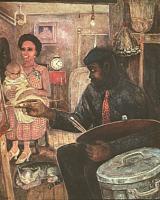

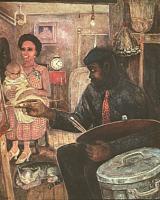

Palmer Hayden, The Janitor Who Paints, 1939-40An especially interesting family portrait in the 20th century is this one by the African American painter, Palmer Hayden. It is a self portrait with his wife and child as a kind of Virgin and baby Jesus. Like Joseph so often in religious paintings, Hayden will be erased in the painting on the easel. In an email to me, Anette Kubitza, art history teacher at UCSB and CSUCI, says "This is actually not a self-portrait of Hayden with his family, but a portrait of his friend and fellow artist, Cloyd Boykin, who was also a janitor. Hayden chose this subject, because no one ever called his friend a painter, but he was called a janitor. So, [it is] likely that he identified with this. Anyway, it is also not clear that the woman and child are the Cloyd Boykin's family. It is likely that they are sitters, who Boykin paints in his modest studio/janitor's living quarter, not untypical for African American artists of that period." |

|

Images of mothers and children are much more common than family portraits. |

Marguérite G�rard's images glorify the mother's role (the wealthy woman of course). Right: The Piano Lesson, 1780s; center: Motherhood, 1804 |

|

|

Because Elisabeth Vig�e-Lebrun was often criticized for being a professional artist, she made a career of painting herself in unthreatening poses, thus disarming her critics and affirming her femininity (Barker 120-27). Here she depicts herself as loving mother; the composition is based in fact on Raphael's Madonna della Sedia, that is on the most innocent and perfect of women and mothers, the Virgin Mary. |

|

|

Left: Elisabeth Vig�e-Lebrun, Self Portrait with Julie, 1789

center: Raphael, Madonna della Sedia, 1514-15 In addition, as Frances Borzello notes, "The visual power of the embrace is convincing evidence of the mother-daughter bond, a useful weapon in this hard-working artist's negotiations with the attitudes of an age that officially 'loved' women but only if they conformed to its notions of femininity" (78). |

In the 18th century Angelica Kauffmann painted this story from Roman history to indicate the selfless love of mothers. Here in Cornelia, Mother of the Gracchi Cornelia responds to her friend. |

The friend has shown Cornelia her jewels and asks "where are your jewels"? Cornelia responds by pointing to her children saying "these are my jewels." I am certain that wealthy husbands in the 18th century continued to give their wives jewels and other adornments (just as some contemporary men do) as a means of signifying their own wealth, but another ethic is proposed here.Angelica Kauffmann, Cornelia, Mother of the Gracchi, 1785 |

|

|

Although Renoir is not known for his enlightened attitude toward women, he painted one of the most gorgeous paintings of a mother with her son and daughter (the son is dressed like a girl). |

|

Renoir, Madame Georges Charpentier and Her Children, Georgette-Berthe and Paul-�mile-Charles, 1878This is bourgeois femininity at its best, the mother is a model of passivity, a beautiful decorative object. |

|

Later artists problematize these sentimental views. Although Mary Cassatt is capable of painting the mother and child theme with as much sentimentalism as any artist (see The Caress below), she also portrays this relationship more objectively. |

Mary Cassatt, The Caress, 1891; The Bath, 1891-2; The Bath, 1890-91, drypoint/aquatint

|

|

|

|

|

And Cassatt depicts her own mother, not as nurturer but as an intellect; here she intently reads the newspaper, not some romance novel.Cassatt, Reading Le Figaro, 1883 |

|

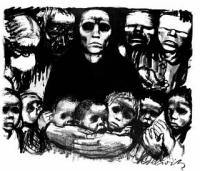

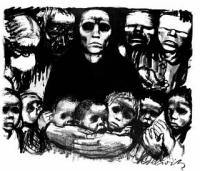

Käthe Kollwitz, who lost both a son and grandson in World War One and Two respectively, recognizes a less glamorous kind of motherhood. Her mothers are stolid figures whose main function is to protect their offspring. |

Left: Kathe Kollwitz, The Survivors, 1923

center: Tower of Mothers

|

|

|

|

The African-American sculptor and printmaker, Elizabeth Catlett, sculpted numerous images of the mother and child, some more or less traditional (see below left)] with fluid, beautiful surfaces. But I find her black marble Mother and Child especially interesting. |

|

|

Left: Elizabeth Catlett, Mother and Child, bronze, 1978

center: Mother and Child, black marble, 1980

|

|

A commentator explains that she "adapted the horseshoe shape of a pre-Columbian belt form to define the arms of the mother in a 'rocker' configuration. The child is nestled under the 'eaves' of the mother's breast, and her head is turned to the side to present a vigilant profile" (Sims 23). Like Käthe Kollwitz, Catlett defines the maternal role primarily as protective.

I'd like to say that a number of artists recognize the important role of the father; however, depictions of fathers and sons or daughters are few and far between. Apparently unlike our first year students, artists haven't read Popenoe's article! A woman artist, Berthe Morisot, does depict her husband with their daughter Julie in several paintings. I don't know whether he was an unusual father to enjoy so much the company of his daughter or whether Morisot is simply unusual in finding this subject worthy of her art. |

Berthe Morisot, Eug�ne Manet and his Daughter Julie in the Garden (The Husband and Daughter of the Artist), 1883 |

|

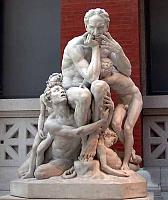

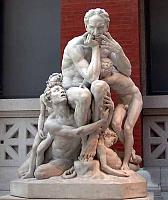

A much more frightening image is of the father Count Ugolino, the main character in a story told in Dante's Inferno. He and his sons and grandsons were imprisoned by an enemy and left to starve. The children, realizing the predicament, offer themselves as food for their father. Four days later, the children die. Six days later Count Ugolino goes blind and "then hunger proved more powerful than grief." Carpeaux, Ugolino and His Sons, 1860-2 |

|

|

I would like to look at a two more contemporary views of motherhood. In Dorothea Tanning's Self Portrait (Maternity), the sentimental view of motherhood is replaced by a frightening surreal image. It is perhaps relevant that Tanning painted this work the year she and Max Ernst, the surrealist painter, married. She consistently refused to have children and instead lavished her attention on their Pekinese dogs. Do we today regard this rejection of the maternal role as abnormal, perverse? |

|

|

Dorothea Tanning's Self Portrait (Maternity), 1946

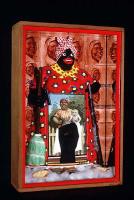

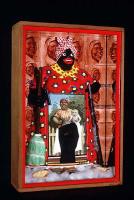

Betye Saar, The Liberation of Aunt Jemima, 1972 |

|

An even more revolutionary image is seen in this work by the African American artist Betye Saar, The Liberation of Aunt Jemima. The artist explains that Mammy was a character invented by white Southerners; this Mammy knew and stayed in her place. Saar says her "intent was to transform a negative, demeaning figure into a positive, empowered woman who stands confrontationally with one hand holding a broom and the other armed for battle. A warrior ready to combat servitude and racism" (Raven 3). Aunt Jemima had been assigned the gender role of mother--to white children in her care. She totes a gun and rebels against this gendered and racist role.

|

|